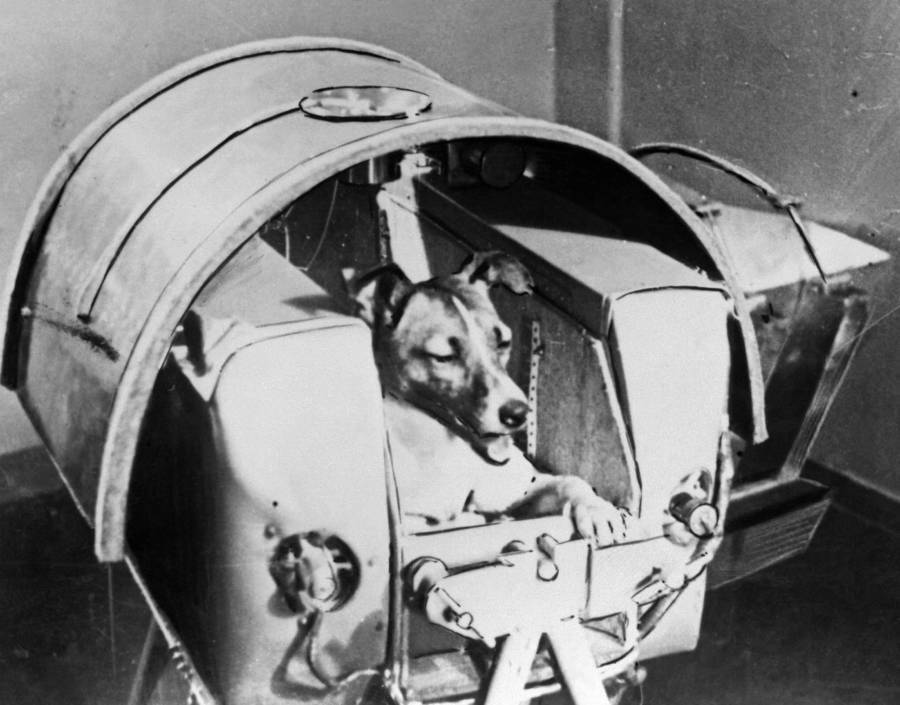

Laika, famously known as “Muttnik,” became a symbol of both scientific progress and tragic sacrifice in 1957 when she made history as the first living creature to orbit Earth—and the first to die in space. Long before Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space in 1961, Laika’s journey aboard Sputnik 2 marked a major milestone in the Space Race between the Soviet Union and the United States. On November 3, 1957, the small stray dog was launched into orbit, never to return. Her mission was celebrated as a triumph by the Soviets, but it also underscored the harsh realities of space exploration during its earliest days.

Laika, whose name translates to “Barker,” was a husky-spitz mix found wandering the streets of Moscow. She wasn’t the only dog in the Soviet space program, but she was chosen for the mission because of her size, temperament, and ability to handle stress. Just one month prior, the Soviets had successfully launched Sputnik 1, the first manmade satellite to orbit Earth. Hoping to maintain their momentum and impress the world—and especially to mark the 40th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution—Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev demanded another dramatic achievement. With very little time, Soviet scientists scrambled to prepare Sputnik 2 and selected Laika for the mission, fully aware that she would not survive.

Laika’s mission was designed to test the feasibility and safety of sending living beings into orbit. While the U.S. and Soviet Union had previously sent animals into space for suborbital flights, no animal had yet made it into full orbit around Earth. Laika would be the first. Her voyage was viewed as a step toward sending humans to space, even though the technology to safely return a living creature from orbit did not yet exist. Her sacrifice was meant to provide crucial data for future missions.

Before Laika, the first animals sent into space were fruit flies, launched in 1947 aboard a V-2 rocket by American scientists to study the effects of cosmic radiation. The flies survived, but the road to safe animal spaceflight was far from smooth. From 1948 to 1951, the U.S. launched numerous monkeys and mice, with many missions ending in fatalities. Albert II, the first monkey in space, reached 83 miles in altitude in 1949 but died on impact due to parachute failure. In 1951, the Soviets launched two dogs, Tsygan and Dezik, who survived a suborbital flight reaching 62 miles. Later, a U.S. monkey named Yorick died of overheating while waiting for rescue on the ground, even though several mice in the same capsule survived.

By 1957, the stakes had risen dramatically. The Soviets were eager to secure another first in space exploration. Although Sputnik 1 had captured the world’s attention, Khrushchev wanted something even more impressive. The solution was to send a living creature into orbit—an animal that could demonstrate the potential for human space travel. Laika, renamed “Muttnik” by the American press as a nod to Sputnik, was chosen. Soviet engineers built a new, pressurized capsule for the flight, complete with life-support systems and sensors to monitor Laika’s vital signs.

Laika was accompanied by two other dogs during training. Albina served as her backup, and Mushka was used for ground-based experiments. In the weeks leading up to the mission, the dogs were confined to increasingly smaller cages to simulate the tight space within the capsule. They were fed a special gel and monitored constantly. Just days before launch, Dr. Vladimir Yazdovsky took Laika home to spend time with his children. He later recalled, “Laika was quiet and charming. I wanted to do something nice for her. She had so little time left.”

On November 3, 1957, at 5:30 a.m. Moscow time, Laika was launched into space. She wore a harness-equipped spacesuit, and her capsule was fitted with sensors to track her heartbeat and breathing. During launch, her heart rate tripled and her breathing rate increased fourfold. She successfully reached orbit and circled the Earth in about 103 minutes. But the joy of this accomplishment was short-lived. The temperature regulation system in the capsule malfunctioned, and the interior rapidly overheated. Within hours, Laika succumbed to heat and stress. Despite this, the Soviet Union initially claimed that she had survived several days, even suggesting she died peacefully from oxygen deprivation or had eaten poisoned food provided as a humane measure.

The truth about Laika’s death remained hidden for decades. In 1993, Oleg Gazenko, one of the scientists who trained Laika, publicly expressed regret, stating, “The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it.” In 2002, further details emerged from scientist Dimitri Malashenkov, who confirmed that Laika had died within hours due to the rapidly rising temperatures inside the capsule. She had not eaten the poisoned food. Her death was not peaceful, but the result of a failed and hastily constructed temperature control system.

Sputnik 2 itself did not return to Earth. It disintegrated during reentry on April 14, 1958, with debris believed to have fallen somewhere over the Amazon rainforest. Despite this grim outcome, Laika’s mission was a key step in the advancement of human spaceflight. It provided data that helped scientists understand how living organisms respond to the stress and conditions of space, paving the way for Yuri Gagarin’s successful return from orbit in 1961.

Laika became a symbol of both scientific progress and ethical debate. In the decades that followed, many people—both in Russia and around the world—recognized the cruelty of sending a helpless animal on a one-way mission. Yet her legacy endured. In 2008, more than 50 years after her death, a monument to Laika was finally erected in Moscow. The statue, shaped like a rocket with a hand cradling a small dog, stands near a military research station. It serves as a tribute not just to Laika, but to all animals sacrificed in the name of progress.

Yuri Gagarin later reflected on his own place in history by invoking Laika’s legacy. “I am still unaware who I am,” he said, “The first man or the last dog.” In a way, Laika was more than a pioneer—she was a martyr of space exploration, and her name will forever be remembered in the stars.